- About us

- Project

- Publications

-

Deliverables

D6.4 – Promotional material

December 31, 2020DeliverablesThe aim of the communication materials is to publicise the COALA Project among potential users. This Deliverab...

D6.2: Communication and Disseminati...

December 31, 2020DeliverablesThis Deliverable is an update of the first version of the Communication and Dissemination Plan.

D4.1: Baseline Description of Pilot...

September 30, 2020DeliverablesThis Deliverable describes the pilot experiments of COALA Project. Participatory evaluation of the COALA servi...

- Media Room

-

News

COALA Project: A Success St...

August 20, 2023Blog, Evidenziato, News, Press ReleaseThe COALA Project, a European Union funded project involving a collaborative initiative between the European U...

Workshop on COALA business model

December 19, 2020News

Plenary meeting November 23, 24 and...

December 1, 2020NewsThe plenary meeting of COALA Project has been held on 23rd, 24th and 30 November 2020

Webinar: Governance of Water Scarci...

November 17, 2020NewsThanks to Copernicus data, Europe and Australia launch a new challenge to improve the management of water and ...

- Blog

- Resources

-

- February 24, 2023

- UNSW

- Blog

- No Comments

Big Data for Agriculture; In Conversation with Francesco Vuolo

Far from the dirt roads and flat landscapes of Australian farmland, Dr Francesco Vuolo calls me from the idyllic mountainous background of Austria. Dr Vuolo speaks with me about the big data for agriculture that COALA uses for its projects, drawing from a wealth of experience working with satellite data.

Based at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna, Austria, Dr Vuolo introduces himself. “I’m Francesco Vuolo. I’m a senior scientist working on remote sensing for agriculture. To tell you a little bit about my background, I’m an agronomist. And I started in Italy, at the University of Naples, and my area was agricultural science. Later, I specialised in using remote sensing for vegetation, more precisely, irrigation management.”

Dr Vuolo was drawn to collaborating on the COALA project by the interesting Australian landscape and the potential for international collaboration.

“I’ve been working on the topic of agricultural management for many years, in Spain, Italy, and in Austria, where I’m now based. There has always been a great attraction to the Australian landscape and market, because of the natural agricultural management conditions in Australia, and through colleagues and long-lasting relationships, science and friendship.”

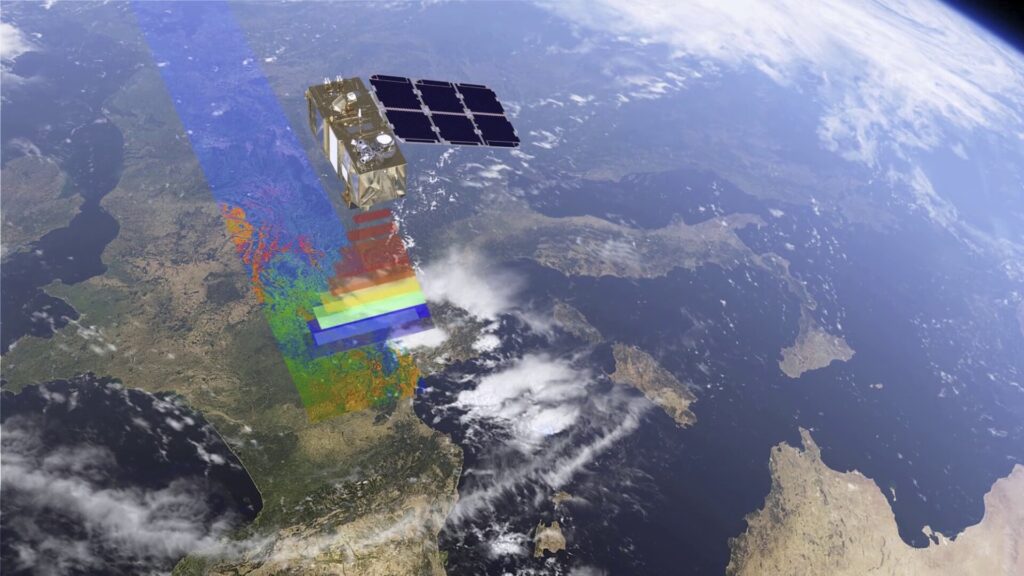

Copernicus Sentinel 2

Dr Vuolo is responsible for the implementation, testing and operation of the Copernics Sentinel 2 satellites on the COALA project. But before we can begin to discuss the functionality of Dr Vuolo’s role, we need to understand what Sentinel 2 is and how it can be used.

“Basically, satellites are like the digital cameras we use for photography. However, satellites can also see spectrum regions that are relevant to vegetation conditions. For example, near infrared and the shortwave infrared. So, with all this information, we can look at the land to understand how vegetation is growing, if it’s healthy, and what needs to grow well and perform well.”

The Sentinel 2 satellites that Dr Vuolo works with generate huge amounts of data, which is why it is called big data. There have been significant advances in the 15 years that Dr Vuolo has been working with earth observation. How we share and access data, or the data policy structure, has dramatically evolved, as has the amount of data available.

“15 years ago, when I started, you had to order the data, you had to pay for the data, and you had to wait for the data. It’s a bit like when we had analogue photography: you would take a photo and then bring the film to the lab for development and maybe a week later, the photograph was printed. And then with digital there was still a timeline, you would wait a week between the acquisition of the satellite image data to the time you would have the data on our desk for processing. A lot has really changed.”

Today, many people would be shocked and frustrated at waiting a week to receive a satellite image. Fortunately for Dr Vuolo and the COALA project, these timelines have tightened. The project can obtain images just three hours old, providing exceptionally accurate time-sensitive information. And, with this change in speed comes also a change in policy.

“At some point in the early 2000s, the [earth observation] community understood that opening up the [satellite image] data archives and making them free will generate huge scientific and business opportunities. And the cost of the data will be repaid by the buy those pieces of opportunity. So the data became free, and we could use this data, and from the use of this data, we managed to generate products and services.”

How does COALA collect data?

But now we have so much data, what can we use it for? How does COALA select the instruments and images best suited to the products and projects?

“Some national services like the United States Geological Survey, or the NASA satellites and the Landsat missions were providing the data that was suitable for land monitoring applications. To back up these existing satellites with more missions were satellites particular to precision agriculture in the European Union. In particular, I’m talking about the Sentinel family of satellites of the Copernicus program. It is a European program to monitor the condition of the Earth’s surface at different times, spatial scales and spectral scales. To do that, they develop what is called the Sentinel constellation of satellites. So there are different Sentinels, 1, 2, 3 and more. Each is looking at a particular area of the land, water and atmosphere system. Sentinel 2 is dedicated to land applications and it has a twin, they fly in a constellation. This allows us to get data every five days so you can expand the impact of these on the potential businesses and applications that we can generate.”

With the increase in data, there is an increased need to manage it. Technology has evolved to match the volume of data the Sentinel program produces. Dr Vuolo has witnessed, first-hand, the change in data management methods.

“When I started with data, it was CD ROMs. Now, it is unthinkable to store this amount of data on CD ROMs, they are too many and too slow to retrieve. This is also what brought me into this area and into COALA. I would say 10 years ago, it was difficult to sort all the CDs and to get the data on my computer to do science. And I asked some of my colleagues what was their interest in building up data infrastructure. Where the data could be automatically downloaded, stored, processed, and then made available in an easy and straightforward way. So, we as scientists benefit from this data archive. This is essentially how I got into this data processing.”

Connecting data and fieldwork

Although we are discussing data management, Dr Vuolo is passionate about the practical application of this data and fieldwork. And, this connection has informed the way COALA runs now.

“I said before, I’m an agronomist, I like to get my hands dirty in the soil. But the data volume was limiting my capacity to exploit the data. And therefore, I think it was 2006, when a paradigm shift was needed. We invested a lot in computers, hardware and software specialists to put together an infrastructure that would work. The project was getting the data set, sharing the data, all automatically, and at the same time maintaining the quality of the data, and combining together all the knowledge that we have, from many years of experience. And we see this now in COALA.”

Once the efficiencies in obtaining and storing the data were perfected, Dr Vuolo began to see huge opportunities for this satellite data. There were opportunities in environmental monitoring but also for freeing up research time and resources.

“I mean the impact of satellite data for other applications is huge. Just to mention some, monitoring forest fires, changing forest conditions, but also longer-term climate variations. For example, some of the indicators that we are consolidating in COALA such as Leaf Area Index or NDVI. Those are needed in climate change studies. There are also implications for infrastructure. We are giving them time by automating the obtaining and processing of the data, giving them more time to look at the quality of the data and developing services and additional businesses from this data. So it’s freeing time for scientists and data producers to do more.”

The future of big data for agriculture

Dr Vuolo has a focus on the outcome of the COALA project. But the end goal for his work keeps shifting and developing as the capability of space technologies change and grow. He laughs as he is asked where he sees the field of space technology progressing and what he thinks the future might hold for this data.

“The answer to these questions is changing with time. Because technology and new opportunities are changing so fast I have to revise and rephrase this answer at several points. I think giving an answer now, I will have to change it again in two years. I think my wish for the future is that the data can really be beneficial for users and that users will fully understand and appreciate the value of this information. For example, today, weather forecasts are well accepted and well-known for all of us. For me, it’s a common practice to look at the weather. In the past, we open the window, we look outside, but we didn’t know what was going to happen in the coming days. And today, with simple apps on our phones, we can see the weather and plan. We can plan our weekends, plan our activities, our farming, our vacations, and so on. And this is how I see what our space technology can offer in the very near future, so much more beyond the weather. We can see how the crops are doing and we can plan more precisely what to do with our crops, what our neighbours are doing and learn, or how much irrigation we need. So it’s not just the top part of the atmosphere and the weather that we can observe. But it’s also the bottom part; how the crops are growing. And the sooner we can transfer this knowledge and, and the value of this information to the farmers, the better would be for them and for us to appreciate and optimise production.”

Through engaging and embracing the ever-evolving field of space technology, Dr Vuolo has stayed at the forefront of the wave of information we can gain from satellites. His passion and expert knowledge has been channelled into the COALA to produce a grounded and progressive tool for Australian growers.